After a 40-Year Career, I’m Back at a New Beginning

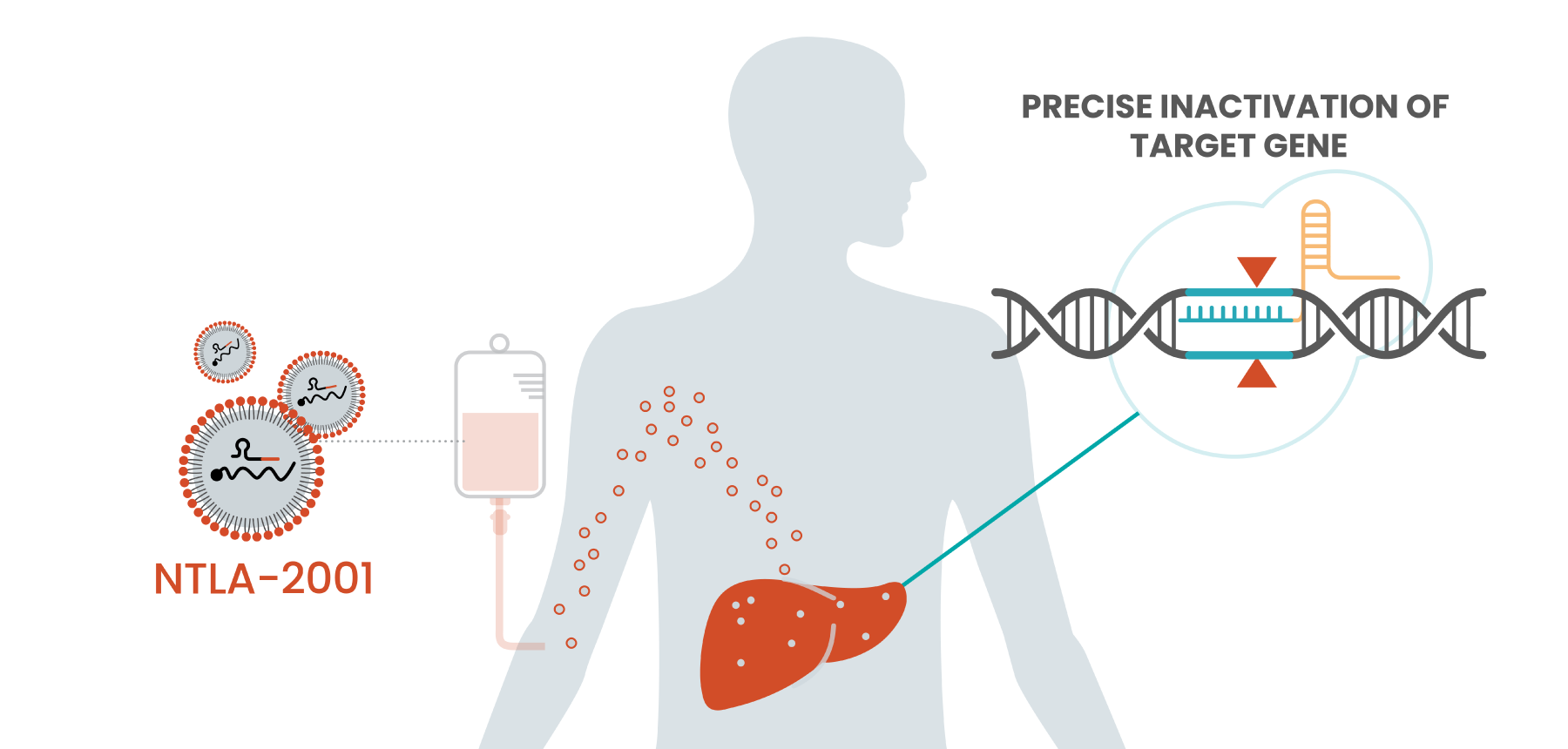

This week, we entered a new era of medicine. Our team at Intellia Therapeutics announced the first clinical data in history suggesting that we can harness the genome editing technology CRISPR to precisely edit target cells within the body. This means we can now treat — and potentially cure — genetic disease with a single intravenous infusion.

This is a historic accomplishment, not just for Intellia, but for the entire medical field. It opens the door to treating a wide range of diseases that were previously thought untreatable.

I’m proud of our team for translating the Nobel Prize-winning science of CRISPR into a therapeutic candidate in only a few short years. This moment belongs to everyone at Intellia: Our incredible team and all our wonderful collaborators around the globe who have made this achievement possible.

But this moment also belongs to the patients. Our new data show that we can potently and precisely inactivate the gene implicated in a rare disease called ATTR amyloidosis. We believe this will not just halt, but reverse, the progression of this fatal disease. This moment, then, belongs to the hundreds of thousands of people living with ATTR amyloidosis — and to the millions more around the world living with other genetic diseases. For them, we open a new era of medicine.

When failure is not an option

When I graduated from medical school almost 40 years ago, this milestone would have been inconceivable to me. We were, after all, a couple decades from learning how to sequence the human genome, much less edit the specific nucleotides responsible for disease. Yet over the course of my career, I’ve come to understand the importance of setting bold goals and believing you can achieve them, even and perhaps especially in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds.

I first learned this lesson early in my career when I treated people living with HIV as a young doctor in California in the early days of the AIDS pandemic. When I think of that time, what I remember most was the powerlessness that I felt. There were no approved HIV therapies in those days, so doctors could do little but watch people suffer. And in the early years of the HIV epidemic, suffer in the shadows.

I could not sit on the sidelines. In 1992, at the height of the AIDS crisis in the U.S., I joined Abbott Laboratories to work on their HIV program. There were only a few of us in that group. Any reasonable outsider would have predicted our chances of success were zero.

And yet, we never thought we would fail — because we knew we couldn’t afford to.

Four years later, we were celebrating FDA approval of our group’s first drug: Norvir, only the second protease inhibitor ever approved for the treatment of HIV. Our next approved HIV treatment, Kaletra, shortly followed. These therapies, and others like them, changed the trajectory of the pandemic. The death rate plunged.

In the years that followed, my teams at Abbott delivered new treatments for hepatitis C, cancer, and autoimmune disorders, including Humira, which is the best-selling drug in the world. When Abbott spun off AbbVie, I became global head of pharmaceutical research and development, overseeing thousands of people and dozens of discovery projects. After three decades, I realized that I wanted to be closer to the science. It was time for something new.

Harnessing the power of CRISPR

In 2013, unemployed for the first time in many years, I first met Nessan Bermingham, a venture partner at biotechnology firm Atlas Venture, who told me he was starting a little company in Massachusetts.

Intellia wasn’t Intellia at the time. It was just a belief — a belief as improbable as the one I held when I first started working on HIV therapies. What if we could turn the promise of CRISPR-Cas9 into a medicine? Future Nobel Prize winners Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier had recently shown that their CRISPR/Cas9 system could be used to edit mammalian DNA. What if we could turn that tool into a medicine capable of precisely editing, removing or replacing a disease-causing gene inside the patient’s body?

The possibilities were tantalizing, but the challenges were immense. It seemed likely — and indeed researchers would soon confirm — that you could use CRISPR/Cas9 to edit human cells outside the body and then return them to the patient. This was a promising path to treat diseases accessible through blood or stem cells. But it was also clear that this approach would not work for the large number of genetic diseases which originate in organs such as the liver or the muscle. Those cells were much harder to access.

To harness the full potential of CRISPR, then, we would have to find a way to deliver it to a specific tissue within the body where it could edit the cells responsible for a given disease.

Bold goals and a growing team

We decided to pursue both approaches at once: ex vivo editing of cells removed from the body and in vivo editing of cells inside the body. As we gained confidence in our science, we built out our team, growing from just a handful of people in 2014 to more than 400 today. These are the individuals who have made the discoveries, negotiated the contracts, filed the patents, balanced the books, recruited the talent – in short, done all the many things we had to do to grow Intellia to where it is today. They are a fantastic group, and I am proud to call them colleagues.

As we expanded and advanced our pipeline, we focused considerable resources on cracking the formidable challenge of in vivo CRISPR delivery.

We knew that CRISPR/Cas9 could make incredibly precise edits inside a cell, but it took several years of research to develop a targeted lipid nanoparticle (LNP) delivery system that would enable those edits in liver cells — where the disease-causing proteins that cause ATTR amyloidosis are expressed. The data we just released confirm that our construct does successfully target that protein, knocking it down by as much as 96% in patients treated with our investigational therapy.

I came to Intellia with the conviction that CRISPR could be more than just a breakthrough at the research bench. That it could be a pipeline of medicines, harnessed to treat previously untreatable diseases and alleviate human suffering.

We still have a long way to go. And yet with this accomplishment, we’ve opened the door. Today, we are one step closer to fully realizing the promise at the heart of the genomic revolution. We won’t stop until we get it done.

And so, as improbable as it may seem, 40 years into my career, I am happy to say that this is only the beginning. This is a new era of medicine.